History, Heritage, Identity: Arabic manuscripts in Cape Muslim Families

By Saarah Jappie

In Muslim households scattered across the greater Cape Town area, sequestered in boxes, cupboards and trunks, there are handwritten books dating back as early as the late eighteenth century. These documents, often aged and dusty, with brittle, yellowing pages, are covered in a script not commonly linked with the “early Cape” – the Arabic script. They were penned by students, schoolmasters, practitioners of mysticism and others in the Muslim community during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and have been handed down and preserved through the generations of Cape Muslim families. These manuscripts are locally referred to as kietaabs, which derives from the Arabic word ‘kitāb’ meaning ‘book’, and are tangible remnants of an active Arabic-based writing culture in Cape Town that lasted until the early twentieth century.

When thinking of Islamic manuscripts in Africa, the town of Timbuktu often springs to mind. Because of academic projects (such as the one I myself am involved in), international media interest and other forces, Timbuktu has become a strong symbol of Islamic writing cultures on the continent. However, the tradition does not end there. Rather, the Arabic script has been, and still is, used by Muslim communities throughout Africa, from Nigeria to Ethiopia and from Zanzibar to Cape Town. It has been used both to write the Arabic language, and to write local languages. In fact, at least twenty-eight African languages have been or are written in the Arabic script. In all of these areas where the script has been used manuscript collections are to be found.

The Arabic writing system was brought to the Cape by slaves, exiles and convicts originating from areas around the Indian Ocean Basin. At least some of these people were Muslim and came from a region were the Arabic script was the dominant mode of literacy, for instance the islands of modern day Indonesia where jawi or Arabic-Malay was used. Because the Malay language was one of the main lingua francas at the Cape, particularly among the Muslim slave, exile and free black population, jawi naturally came to be used as its written counterpart. However, (proto)Afrikaans later replaced Malay as the lingua franca and, by the mid-nineteenth century, jawi was replaced by Arabic-Afrikaans. Both of these scripts were taught through the madrasah education system, which was one of the only forms of education available to Muslim children at the time.

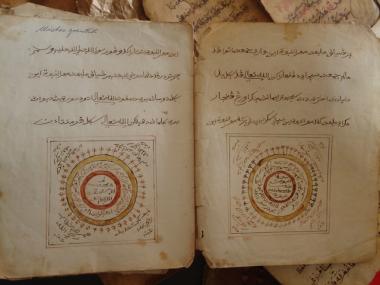

Based on available extant texts, we find that the majority of kietaabs are educationally inclined. They are either handwritten copies of popular Islamic texts on jurisprudence and faith that were circulated in the Muslim community, or they are koples boeke – the notebooks that madrasah students would write their class notes in. In addition to these texts we find talismanic manuscripts. These can include books with prayers accompanied by talismanic formulas, and also kinds of talismanic ‘manuals’ that include instructions on how to create different amulets and which formulas to use for specific problems. Besides actual ‘books’ there are also handwritten letters and personal inventories written in ajami script, however these are quite rare.

From their contents, it is clear that these documents had very practical uses – some were circulated as texts containing religious information, others were written in and read in the madrasah setting and others still were referred to for mystical purposes. However, when these practices became less common, and when handwritten books were replaced by printed ones – initially in Arabic script and soon after in the Latin script – the kietaabs ceased to be used, except as heirlooms as we see in cases today.

The manuscripts that are held as heirlooms in families across Cape Town are but a fraction of the number that once existed and it is believed that many – if not most – kietaabs were either lost or destroyed over the years. Those that survived generally did so because they were considered to be part of the family history, as objects linking the family to their ancestors. They have been consciously passed on through the generations and often closely guarded.

The kinds of family narratives that the kietaabs represent are diverse. For some people, they are part of the strong Islamic heritage of the family. This may be because certain manuscripts belonged to a particular well-known scholarly ancestor who used the kietaabs in their work as a religious teacher or scholar. Or, in other cases kietaabs may have been inherited from an influential religious scholar who was not necessarily a family member, but who a family member studied under.

For others, the significance is more on a cultural level, as objects of a Southeast Asian cultural legacy. To be precise, for an emerging number of Muslims in Cape Town interested in their family history and heritage, the manuscripts have become archival sources ‘proving’ a specifically ‘Malay’ identity. In extreme cases, based on genealogies included in manuscripts, families or individuals have traced their origins to a specific individual or geographical area in Southeast Asia. A classic example of this is the Rakiep family, the descendants of the iconic figure Imam Qadi Abdul Salaam, known as “Tuan Guru”, a political convict imprisoned on Robben Island in the late eighteenth century, who went on to establish the first mosque in South Africa in 1794. Through a particular manuscript, the family happened to trace their lineage straight to Tidore, eastern Indonesia, the birthplace of Tuan Guru.

However, more commonly, possessing manuscripts in jawi has become a more general marker of ‘Malayness’. Although in these cases kietaabs cannot link the individual or family to a specific ancestral story, they do connect them to a broader narrative of a Southeast Asian presence in Cape Town. As some see it, because someone possesses kietaabs written in the Malay language, they are necessarily able to claim ethnic ‘Malay’ ancestry.

The use of the kietaabs as objects of ancestral evidence points to broader issues of archive. As the descendants of slaves, exiles and other subaltern peoples, it is a challenge for many Muslims in Cape Town today to find official archival sources that provide clues as to their family origins. Therefore, alternative sources are sought after in order to stabilise some sense of family heritage. In this context, the kietaabs have come to be an alternative piece in the ancestral puzzle.

Saarah Jappie is a researcher in the Tombouctou Manuscripts Project. This article first appeared on the Archival Platform website.