From Cape Town to Timbuktu, A novice Traveller’s Reflections, Part 2

By Mbongiseni Buthelezi

Those who are familiar with Jamaica Kincaid’s work, especially A Small Place (1998), will have noted the reference to natives and tourists as well as colour, and the register in which these references were made as nodding in the direction of her book. This time round Joseph Conrad is at the back of my mind. Soon you’ll see how. In the last piece you got a glimpse of us, the natives of somewhere else, visiting manuscripts libraries, mosques and an artisan’s studio. In the evening, dust covered and exhausted, we lumber into La Maison hotel to sup on the delights that were on offer that night.

The Workshop in Timbuktu

The next two days are to be a revelation. For starters, Seydou Traoré amazes with his linguistic skills and the agility of his mind – moving in and out of Arabic, Songhai, English, French, Bambara, and even some Afrikaans. He makes each paper presented understandable to all in the room across the linguistic gulfs that separated us. The conversation at the Mama Haidara Centre is slow and laboured throughout the two days, but it still flows somewhat smoothly. We discuss what the content of the manuscripts in the family libraries of Timbuktu was and the preservation of the manuscripts. It is striking to learn how scholars in Mali work. Our colleagues from Timbukutu each present a paper on one manuscript. They have studied the manuscript extensively: as far as they can determine what its provenance was, who the author was, and the manuscript’s circulation, including how many copies of it exist in different libraries.

With my interest in oral literature, I am intrigued to learn that written culture was the preserve of scholars and learned families in the long past. It functioned in Arabic, but griots would popularise some of the texts, translating them into Songhai, Bambara and other languages. The manuscripts of Mali give the lie to the myth of Africa the oral continent that has perpetuated in scholarship until recently. I am surprised by the force with which the realisation hits me how deeply I had bought into this myth. While I had read and heard many a time that Africa had long traditions of writing, it took being in Timbuktu for it to hit me in the face that this was actually true. It’s one thing to read books and journal articles about a subject. It really is something altogether different to be there in a place that could very well have been on the dark side of the moon. There you simply feel the weight of centuries and centuries of the accretion of thinking, of knowledge and of lived experience. And so you know the things you’ve known only in your head before in a different way. You know things in an embodied way. I even struggle for words to say what I experienced in Mali. Just being there at the edge of the Sahara, far away from anything I have known before, from the ways of living with which I am familiar, was a pivotal experience. There’ll now always be before Mali, before Timbuktu and after.

But I digress again. Back to the story of the workshop: the South Africans and Amidu Sanni from Nigeria share their experiences in the archiving and digitisation. There are talks on the James Stuart Archive, on digitising the Bleek and Lloyd collection, on Africa in the global world of museums and on South African literature written and oral.

At the end of the three days in Timbuktu we are all zonked out. Several express the desire to simply vegetate for a day. And vegetate we do the following day, the 19th of January. We could not have wished for better than to sail down the Niger River in glorious weather. It takes another early morning flight from Timbuktu to Mopti to get to the river to catch the boat. At first some of us spend the morning being grumpy. It takes some breakfast and lots of coffee to cheer me up, at least. From there the day just gets better and better. We are mobbed when we get down to the river bank by people trying to sell us things. Here, like in Timbuktu, almost everything is sold in the street. The market is informal for the most part. Nothing has a fixed price. You negotiate the price of anything that catches your eye. In Timbuktu, an army of traders waited for us each morning and each evening. Word had got out the day we had arrived that there were tourists in town. So every morning and evening we were cajoled to buy Tuareg jewellery, daggers, camel skin bags with great stories of how the money would go towards helping feed relatives and their camels in the desert. Once we’d heard the same story a few times we figured out that it was just a nice concoction for the bleeding-heart tourist.

Down the Niger

We climb into our two pirogues. The boats look similar to those one sees in the travels-and-adventures-in-West-Africa-type books from the 18th century: long and narrow, benches around the edges and tables in the middle, hoods overhead. The only thing that looks different is that today the boats have Yamaha engines at the back. There is considerable traffic in this part of the river: water taxis ferrying people back and forth across the river. The trip down the Niger is simply splendid. We recline, read books, take photographs like good tourists and go to sleep. From time to time one of the guys taking us down the river offer us Tuareg tea – half a tot glass of potent stuff that I drink once and my head goes into a spin. I cannot observe the Tuareg tradition of drinking three rounds of it. The first round is enough.

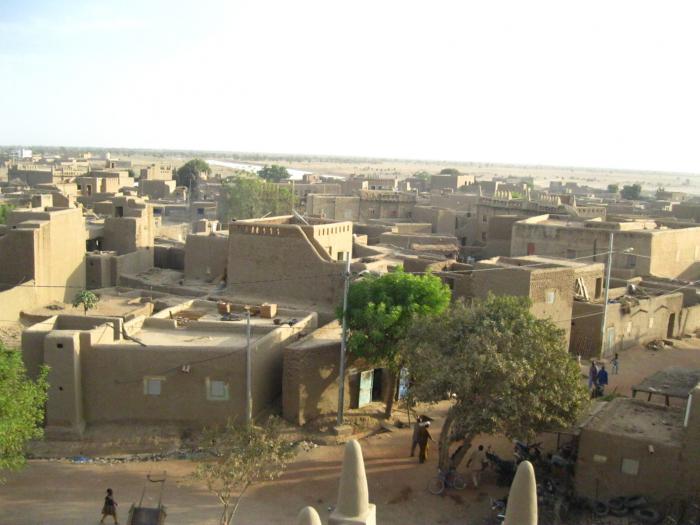

Unlike Conrad’s Marlowe, we do not steam up the river. The plucky little Yamaha engines labour valiantly to propel us down the very still river. We pass villages on the side of the river that looked like sketches from the travels and adventures books – neatly laid-out villages of mud brick houses with perfect walls around them. All brown, brown and brown, turning grey in parts because of the colour of the earth. Our two boats are now a few hundred metres apart avoiding sand banks, now running abreast and things are passed from one to the other. A scrumptious lunch of fish, rice and vegetables is cooked on an open fire right there at the back of the other boat, in full view of the passengers, by the only woman on the staff of these boats. The heaped plates of food are passed over to our boat for us to eat ourselves silly. And we do.

The thoroughly enjoyable trip turns even more so as the sun descends and darkness begins to fall. The sky turns crimson and orange. And like good tourists we snap diligently away at it with our cameras. The trip turns entertaining and then farcical by the end. When we approach what looks suspicious, a guy runs to the front of the boat, pulls out a long pole and sticks it into the water to make sure there is no sandbank ahead. We hit our first sandbank as the darkness settles; the engine is able to push us clear. And then we hit another one. This time the guys have to jump onto the sand bank and shove and pull the boat to get it clear. Now it really feels like being a colonial official or an employee of one of those trading companies that sailed people along these rivers until the end of colonialism. I cringe watching these guys, to whom we have not even said a hello because of language barriers jump, in the water. I put a hand out and feel the water. It’s freezing. But in the end we make it to Djenné alright.

Djenné

In Djenné the following day we visit the town’s library. It’s a public holiday, but the staff has all come to work. We all introduce ourselves. After endless attempts to get the protocol right – who should sit where, who should speak when and the like – we settle into our seats. A few speeches are made. Fousseyni Kouyate from the Mamma Haidara Centre in Timbuktu who came down with us conducts a workshop for the staff on constructing boxes with acid-free materials in which to keep the manuscripts. While he does that we are given a tour of the library. Here in Djenné the families from the town and surrounding areas keep their manuscripts in cabinets in the library. The initial agreement was that the families would keep the keys to the cabinets. But soon the families and the library staff developed enough trust for the families to leave their keys in the library.

We then walk down the road to view the library of the Imam of the local mosque. He has set up his own private library. It has his family’s manuscripts in one section. In another it boasts a whole lot of books donated by the American embassy. You see, the Malians are good Muslims, so the Americans work with them to promote intercultural understanding. Hence the books on the mosques of New York, on Islam in the United States and the like.

The highlight of this visit is the end of the day: a tour of the Great Mosque of Djenné followed by a quick breeze through the Djenné-Djenno archaeological site. Standing on the roof of the mosque looking out over the town feels like being in a dream. The late afternoon sun makes the landscape and the various tributaries of the Niger look unreal, as if they are Photoshopped images really. And then we rush up to where the old town of Djenné was before the onset of Islam and the development of trade. Djenné is said to be the most ancient city in West Africa, founded about 250 BCE. The ruins we view are shards and shards of pottery scattered over a large area. The most unreal is a big pot that shows how people were buried in the town. The skeleton of a human being lies exposed on the ground. The top half of the pot has been worn away by the elements. There the skeleton is in perfect order: the skull and the backbone, an arm and a leg in profile. We fantasise about being ‘discovered; thousands of years hence in our own graves just like this.

On the 21st of January it’s back to Bamako for an afternoon and then onward home to the place we are natives of. It has never been harder to leave a place.

Mbongiseni Buthelezi is the Archival Platform Ancestral Stories coordinator.

Originally published on the Archival Platform website.