ASA panel explores multiple meanings of Islamic libraries in Africa

Rebecca Shereikis, ISITA

“The Islamic Archive of Africa,” an ISITA-sponsored roundtable at the African Studies Association’s November meeting in Baltimore raised important questions about the meaning of Islamic archives and collections in Africa. The panel brought together senior and junior scholars who have used manuscripts extensively in their own research.

The imperiled state of many Islamic manuscript collections in Africa—some threatened with sudden destruction due to political instability (as in the recent case of Timbuktu) and others facing a slower deterioration due to lack of resources and neglect—provided the context for the panel. While acknowledging the importance of preservation and safety of manuscripts, especially in volatile political climates, the panelists demonstrated the importance of viewing manuscripts, not simply as isolated objects to be preserved individually, but as parts of collections with their own histories of ownership, usage, dispersion, and reassembly. Each panelist presented the challenges of disentangling the multiple meanings of the collections they study. As such, the panel contributed to the growing research on writing, book production and circulation, and textual culture in Africa.

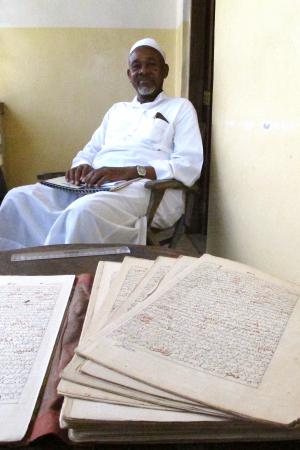

Panel organizer Anne Bang (Chr. Michelsen Institute) discussed two East African collections, one institutional and one private, both links in the chain of intergenerational transmission of knowledge in the region. The manuscripts kept at the Riyadha Mosque in Lamu, Kenya, the longest continuously-functioning Islamic teaching institution in the Swahili world, have been used by students for over a century and are crucial to understanding the historical orientation of Islamic education in East Africa. The private collection of Zanzibari scholar and religious leader Muhammad Idris Muhammad Salih (1934-2012) is of immense value to scholars due to its totality, but Maalim Idris built the collection primarily to help young Zanzibaris access their history, since teaching about Islam was banned in schools after the Zanzibar Revolution. Susana Molins-Lliteras (University of Cape Town) discussed the Fondo Ka’ti, the private library of the Ka’ti family in Timbuktu, which traces its origins to Andalusia. One of the library’s most valuable features is the marginalia inscribed on manuscripts, recording a family history of exile, reunification, and dispersion, along with events of the day. Her presentation demonstrated how the act of assembling a collection to preserve history is actually an intervention in the production of history. Ridder Samsom (University of Hamburg, Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures) described the Al-Buhry collection in Tanga, Tanzania, a small private collection built by former qadhi Ali Hemed Abdallah Al-Buhry (1889-1957) and part of which is now in one of his son’s custodianship. Among books, pictures, magazines, and various manuscripts in Arabic and Swahili, this collection contains a 402 page manuscript with a tafsir of the first six chapters of the Qur’an written by Sheikh Ali in Swahili in Arabic script. Samsom posed questions about ownership of the dispersed collection (while it is clearly a “family” collection, the definition of “family” can be contested), who uses it and for what purposes, and how the library and various items in it are perceived by the wider community.

The case studies offer just a sampling of the range of Islamic libraries in Africa and the various idiosyncratic purposes for which such collections are built and used. Panel chair Scott Reese (Northern Arizona University) observed that while academics have traditionally viewed libraries and collections as storehouses of knowledge to be mined for their own research, each collection retains a variety of meanings for the owners and for local and trans-local Muslim communities. Presenters and audience members also spoke of a tension between modern cultural heritage discourse, commonly invoked by those seeking funding for manuscript initiatives, and the intentions of those who assemble libraries—such as preserving continuity in Islamic knowledge transmission (in the cases of Maalim Idris and Al-Buhry) or reconstructing a family history (in the cases of Fondo Ka’ti and Al-Buhry). To what extent has the adoption of cultural heritage discourse in order to access resources affected the functions of private collections as vital links in the chain of knowledge transmission? Some of the collections, moreover, are important sources of income for the owners in resource poor environments. How do we reconcile—or can we—these myriad and often competing agendas and needs, or the multiple meanings of “access” (which has quite a different connotation to a university researcher than to a religious scholar or student, and yet another to a tourist)?

Acknowledging the complexity of the questions at stake, the panel did not offer easy answers, and clearly there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution. Participants agreed, however, that serious attention to these sensitive issues—and the creation of forums for open and inclusive discussion of them—must be an integral part of planning and implementing manuscript projects on the continent.