Poets Talking

Abubakar Sadiq Abdulkadir

Boasting and pun are some of the features found in the verses of many Arabic poets. In this short piece, I attempt to draw attention to the ways in which poets communicate with their verses by highlighting creative thought and wordplay.

The celebrated pre-Islamic odes (mu‘allaqat) contain many boastful displays of courage and bravery, especially the ode (qaṣīda) of ʿAntara b. Shaddād. The same could be said about Abū Ṭayyib al-Mutanabbī, a prolific poet of the court of the Abbāsid King, Sayf al-Dawla (d. 967). Mutanabbī’s verses are filled with boasts about his knowledge and literary supremacy over others, especially Abū Firās al-Ḥamdānī (d. 968), his arch opponent, for example:

Ana al-ladhī naẓara al-aʿmā ʾilā ʾadab-ī

Wa asma’at kalimātī man bihi ṣamamu

Al-Khaylu wa-l-laylu wa-l-baydā’u ta’rifunī

Wa al-sayfu wa-l-rumḥu wa-l-qirṭāsu wa-l-qalamu

I am the one whose literature is seen by the blind

And my words are even heard by the deaf

The horse, the night and the desert all know me

So do the sword, the spear, the paper and pen

In terms of puns and wordplay, many poets display their erudition by using rare words, unusual meanings, and homonyms. For example, the jīmiyya (verses ending with the alphabet jīm) of ʿAbd Allāh b. Fodio, one of West Africa’s 19th-century scholars, in praise of one of his teachers, Jibril ‘Umar begins with:

ʿUj naḥwa aḍwāji ‘l-aḥibbati min Maji

Wa ‘shrab min al-anshāji mā’a ‘l-zi’baji

Thujja ‘l-dumū’u ‘alā manāzilihim bihā

Wa ‘shfi ‘l-janāna min al-humūmi ‘l-dummaji

Qif ‘indahā sal man bihā ‘asā tujab

Ḥawjā’ aw lawjā’ turḍī man shaji

Turn towards the waving streams of the loved ones of Maji

And drink from the river’s water of the white cloud

Let tears flow on their dwelling place

And cure the heart of the sorrows that occupies it

Stop by them, ask those who live in them, perhaps

Need or want will be answered, thereby giving pleasure to the one who mourns

The verses above do not only illustrate Ibn Fodio’s complex wordplay, they also demonstrate the application of ilm al-badīʿ, a rhetorical science used by Arabic-language poets to give style and polish to their verses.

This rhetorical science is also concerned with the expression of ideas, in which wordplay, colourful and memorable metaphors and examples, logical argument, practical wisdom, metre and rhyme all combine to create a vivid and powerful poetic point. For example these five verses are oft-recited verses as an example of badīʿ:

Ra’aytu ‘n-nās qad ‘adalū ilā man ‘indahu ‘l-‘adlu

Wa man lā ‘indahu adlu fa-‘anhu ‘n-nās qad ‘adalū

Ra’aytu ‘n-nās qad mālū ilā man ‘indahu mālu

Wa man lā ‘indahu mālu fa-‘anhu ‘n-nās qad mālū

Ra’aytu ‘n-nās qad dhahabū ilā man ‘indahu dhahabu

Wa man lā ‘indahu dhahabu fa-‘anhu ‘n-nās qad dhahabū

I realise that people are only just to the one who is just

And whoever is not just, verily people will not show him justice

I realise that people incline only to the one who has wealth

And whoever does not have wealth, far away people will remain from him

I see people flee to the one who possesses gold

And whoever does not have gold, indeed people would flee away from him

The verses above show how the author expresses a stylistic and prosodic know-how of badī’ in the construction of the verses. The verses thus include features of belle-lettres and perhaps an acute observation of human nature. While the intent of the poet could be to draw one’s attention to what he has observed in humankind, one could perhaps also enjoy the wordplay and construction of metres with the end-rhymes: “being just” (ʿadalū) and “justice” (ʿadl), “to incline” (mālū) and “wealth” (mālu), “to go to” (dhahabū) and “wealth/gold” (dhahab), and the varying use of ra’aytu, fa-ʿanhu, ʿindahu and ilā man is highly creative.

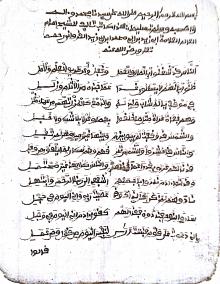

Another highly-regarded work of poetry that is often chanted and taught in many traditional centres of Islamic learning in West Africa is ascribed to an anonymous poet. It is commonly found in West African libraries and collections. The poem is known by its opening line, al-nāsu qad shaghalū, and is regarded as an example of good style and composition. It reads:

Al-Nāsu qad shaghalū bi’l-māli wa’l-amali

Wa ghafalū ‘an ṭarīqi ‘l-‘ilmi wa’l-‘amali

ẓannū bi-annahum lā yus’alūn ghadan

ʿammā janāhu min ‘l-athām wa zalali

Busy are people pursuing wealth and unrealistic hope

But are heedless of the path of knowledge and good work

Thinking they would not be questioned tomorrow

About what they did of sinful acts and wrongdoing

On this note, I leave you with a taste of two verses I composed years ago.

Sarā ṭayfu man ahwā fa afnā bi-ya ‘l-karā

Zamānan fahal yujdī gharāman akhū jawā

Fa-ʿālajtu wajdan lā uṭīqu tajalludān

Kamāshin ʿalā jamrin bi-hi ‘l-shawq dhā dawā

Boasting, pun, prosodic mediocrity or you don’t know? How you understand the verses is your judgment. The ball is in your court.